Medical breakthroughs in 2025

... and a happy new year.

If you fell unconscious in 1950, no one around you would know how to perform CPR: it wouldn’t be invented for another 10 years.1 Or take type 1 diabetes, where survival would involve injecting yourself every day with a thick glass syringe of insulin that was extracted from animal pancreases (with tens of thousands of animals required to produce each pound of insulin). And hundreds of thousands of kids worldwide would catch polio each year, leaving them paralyzed, often needing an iron lung to help them breathe.

Fast forward another thirty years to 1980, and polio would be eliminated in many rich countries through vaccination. Smallpox would be eradicated worldwide. Insulin could now be manufactured by yeast in bulk in bioreactors, and emergency care would look completely different: with implantable pacemakers, AEDs, and coronary bypass surgery.

But you could still die from cancers caused by stomach ulcers, which we now know are typically caused by H. pylori infection and treatable with antibiotics. Or take hepatitis C – a deadly infection that causes liver fibrosis and cancer – which is now curable with antivirals in around 98% of patients.

Some of the most fatal conditions we’ve known, like HIV/AIDS and cystic fibrosis2, are also now highly treatable; taking early treatment for them returns people to near-normal life expectancies. Insulin treatment has advanced to the point that small wearable devices can monitor sugar levels in the blood and release insulin to stabilize them in real time.

But when I read most science journalism, hardly any of it mentions these achievements, the stream of innovation,3 or explains what is still untreatable and why. There's instead far too much hyping up of preliminary studies – what caused/cured cancer in six mice, for example – and much less about what’s changing people’s lives right now, let alone how much people’s lives have changed over the decades.

So, since last year, I’ve been writing round-ups of the biggest breakthroughs in medicine and putting them into context to give you a sense of where we are. Here’s a link to my post from 2024 in case you’re interested.

I’ve split this into three sections – the first section only includes the results of large randomized controlled trials for new drugs published in papers this year, which are closest to becoming available. The second section is about record-breaking achievements and the first patients to receive new treatment methods. And the third section is about lab research that could soon have a big impact in medicine. Finally, a personal note.

This post is long and won’t fit in an email. As usual, I’ll pay you if you spot an error in this post, except for minor typos or grammatical errors. Please let me know if you find one, so I can fix it.

Clinical breakthroughs

Suzetrigine (‘Journavx’) became the first non-opioid painkiller for surgical treatment in decades. In a phase 3 trial of 2,000 patients, it reduced pain as effectively as hydrocodone and paracetamol, but had fewer side effects and doesn’t appear to be addictive. Michelle Ma has written a great article about the history of pain medication leading up to it.

The second chikungunya vaccine (‘Vimkunya’) was approved in the US and EU; it’s a recombinant ‘virus-like particle’ vaccine. Chikungunya is a disease spread by mosquitoes that is similar to dengue: both can cause weeks to months of joint pain and in rare cases, paralysis. I recently had the vaccine myself because I travel somewhat frequently to India, where chikungunya outbreaks are common; all I got was a slightly sore arm.4

Several new lipid-lowering treatments are succeeding in large clinical trials. Some involve designing small interfering RNA (siRNA) to block specific genes from producing their proteins, with just a single injection that has effects for half a year or more.

Obicetrapib. It cut LDL cholesterol levels by an additional 30% in people with a history of heart disease or familial hypercholesterolemia, who were already on the maximum doses of statins and other cholesterol lowering drugs, in a phase 3 trial of over 2,500 people. The drug inhibits the CETP protein, which moves cholesterol between lipoproteins and the blood.

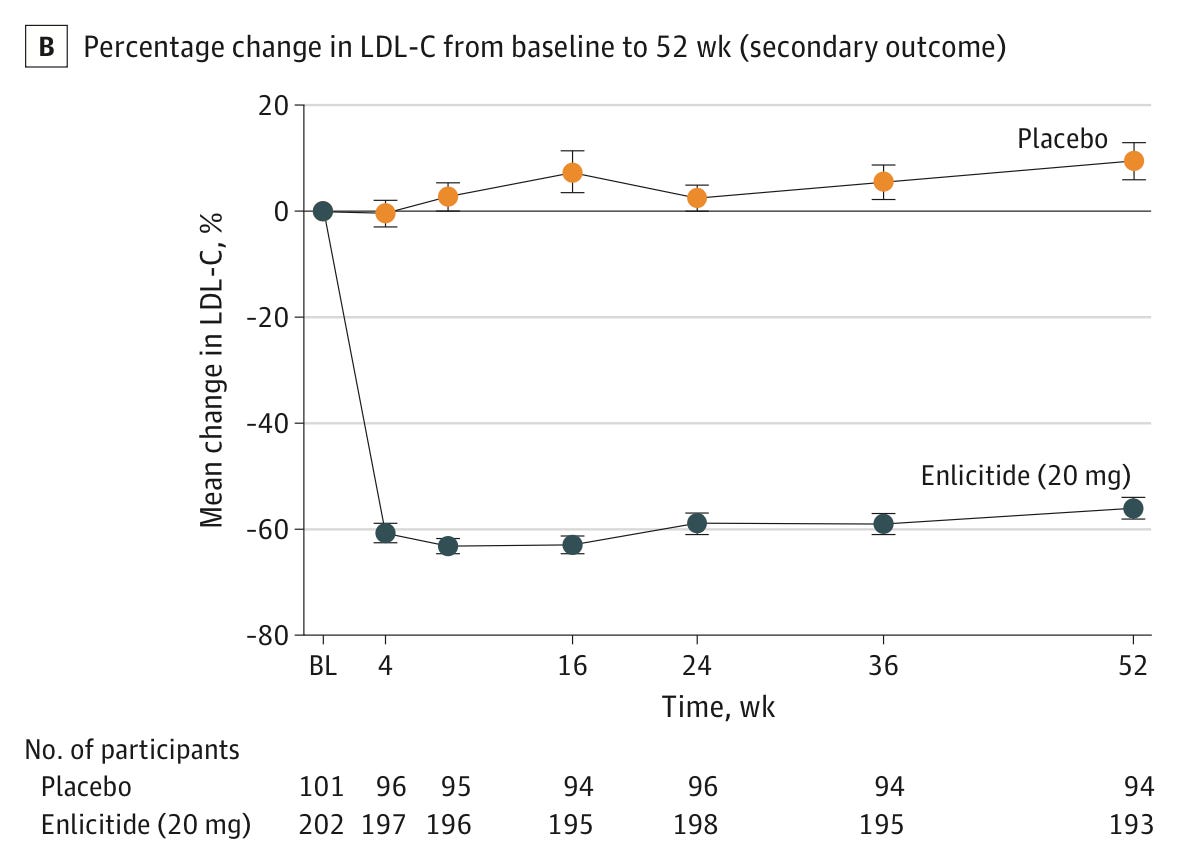

Enlicitide. It cut LDL cholesterol by an additional 59% in people with hypercholesterolemia who were already taking statins or other lipid-lowering drugs, in a phase 3 trial of over 300 people. Merck is now testing its effect in a broader population. The drug inhibits the PCSK9 protein, which regulates LDL cholesterol uptake and has been a popular target for new cholesterol drugs, but enlicitide is the first to do so in pill form.

LDL cholesterol levels in the phase 3 trial for enlicitide in over 300 people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, meaning they had an inherited risk for very high levels of blood cholesterol. People taking enlicitide had a 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol compared to the placebo group, 24 weeks after the trial began. Source: Christie M Ballantyne et al. (2025). Olezarsen. It cut triglyceride levels by 50–70% and reduced the rates of pancreatitis episodes by around 85% in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia in a phase 3 trial of over 1,000 people. The drug is an antisense oligonucleotide taken by injection each month, and works by blocking the formation of the ApoC3 protein.

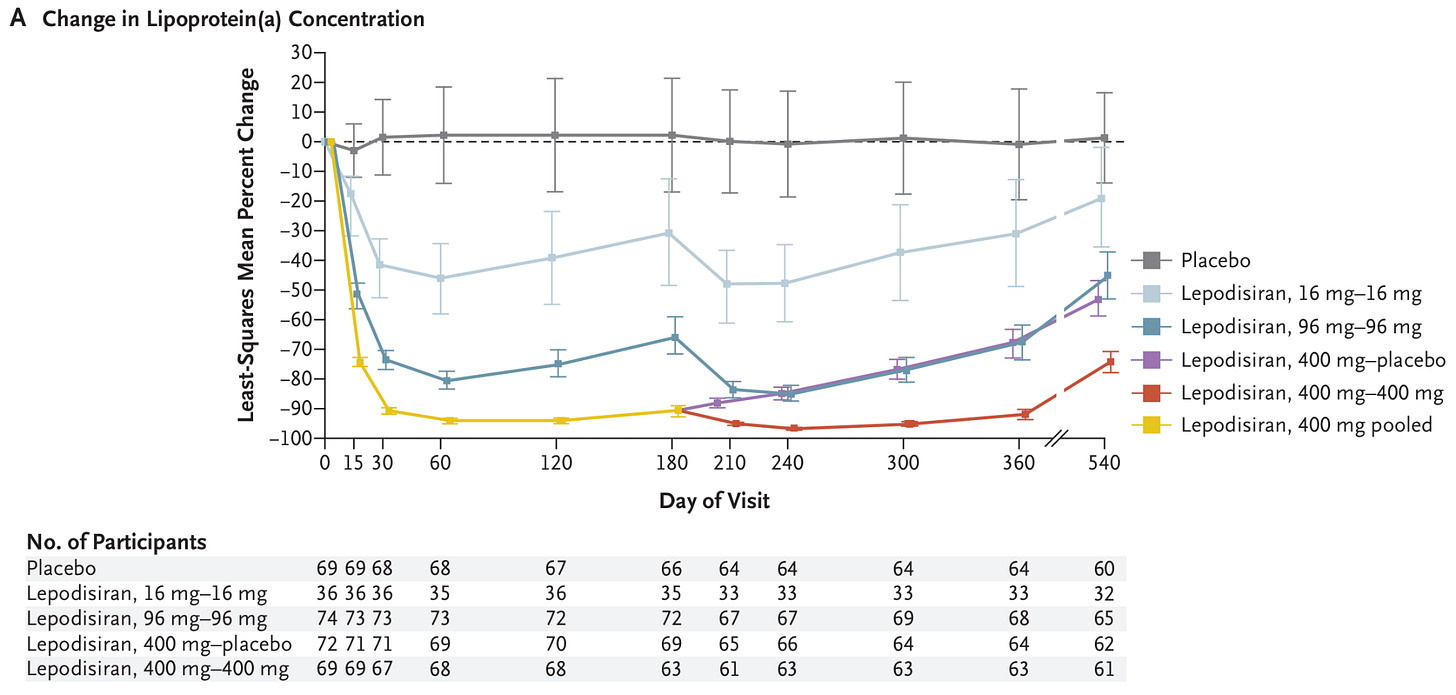

Triglyceride levels in the phase 3 trial for olezarsen in over 1,000 people with severe hypertriglyceridemia, meaning they had triglyceride levels over 500 mg/dL. People taking olezarsen (50mg) had a 63% reduction in triglyceride levels compared to the placebo group, and those taking 80mg had a 72% reduction, 6 months after the trial began. Source: Nicholas A Marston et al. (2025). Lepodisiran, an siRNA drug, causes a dramatic reduction in lipoprotein(a) levels. In a phase 2 trial of over 300 people with very high levels of lipoprotein(a), a single injection of the highest dose (400mg) reduced their lipoprotein(a) levels by 94% and kept them low for months. Their phase 3 trial is ongoing and expected to be completed 4 years from now.

The change in lipoprotein(a) concentration in the phase 2 trial for lepodisiran in people with very high levels of lipoprotein(a), which is like LDL-cholesterol, another risk factor for atherosclerosis. People taking lepodisiran (16mg) had a 41% reduction compared to the placebo group, and those taking 96mg had a 75% reduction, and those taking 400mg had a 94% reduction, 2–6 months after the trial began. Source: Steven E Nissen et al. (2025). A new long-acting treatment (‘Qfitlia’ or fitusiran) for haemophilia was approved. Patients tend to rely on regular infusions of clotting products or similar products to prevent excessive bleeding. This new treatment is also an siRNA, and is given by injection roughly once per two months. In phase 3 trials, it reduced bleeding episodes by around 70% more than standard treatment.

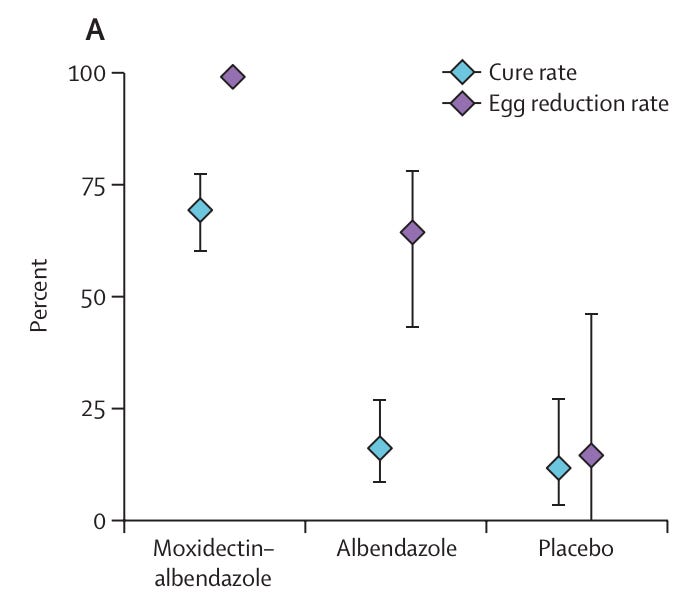

A new cure for whipworm infections, moxidectin-albendazole. In a phase 3 trial of around 270 children in Tanzania, a single combination of moxidectin and albendazole cured 69% of whipworm infections, meaning they no longer had detectable worm eggs in their stool, compared to 16% with albendazole alone.

The cure rate and egg reduction rate for whipworm infections in children in Tanzania, 2–3 weeks after taking the treatment. In the moxidectin-albendazole group, 69% of children were cured of whipworm; in the albendazole only group, 16% were cured; in the placebo group 12% were cured. Source: Annina Schnoz et al. (2025). A new antibody treatment for multiple myeloma called teclistamab led to large improvements in phase 3 trials. So far, CAR-T cell therapies have improved the situation for patients with multiple myeloma, but they are very expensive and time consuming. This new off-the-shelf antibody treatment could offer a more scalable option that’s still highly effective. It reduced the chances of disease progression by around 83% in patients who had relapsed into myeloma and improved their overall survival, when taken as a combination with daratumumab, which has synergistic effects, compared to the standard alternate treatment.

The percentage of patients who survived without disease progression over time in the phase 3 trial for teclistamab-daratumumab. In the teclistamab-daratumumab group, 83% of patients survived without the cancer progressing to the next stage; while in the control group (taking daratumumab, dexamethasone plus pomalidomide (DPd) or bortezomib (DVd)), only 30% did. Source: Luciano J. Costa et al. (2025). A portable test for tuberculosis infections was developed. It’s a handheld device that detects DNA from the bacterium that causes TB and gives results in under an hour. It has higher sensitivity than other methods, and also meets specificity thresholds set by the WHO.

The UK became the first country to offer a vaccine against gonorrhea, as a targeted roll-out for gay men. The vaccine isn’t new: it’s the meningitis B vaccine, which provides some cross protection against gonorrhea, caused by a closely related bacterium. Protection in trials so far has been moderate: one dose offered around a 26% reduction in the chances of infection, while two doses boosted that to 33–40%. But the NHS estimates that, with high uptake among gay men, it could prevent up to 100,000 cases of gonorrhea over the next decade.

New diabetes and weight loss drugs are on their way. Orforglipron is a new GLP1 drug that can be taken orally. Although it’s less effective than other GLP-1 drugs like tirzepatide, what sets it apart is that it is not a peptide, but a small molecule drug that can be synthesized chemically. This should make it cheaper, easier to scale up, and possible to take without needing to time it with meals. In a phase 3 trial of over 500 participants with type 2 diabetes, it reduced body weight by 4.5 to 7.6%, depending on the dose, in 40 weeks.

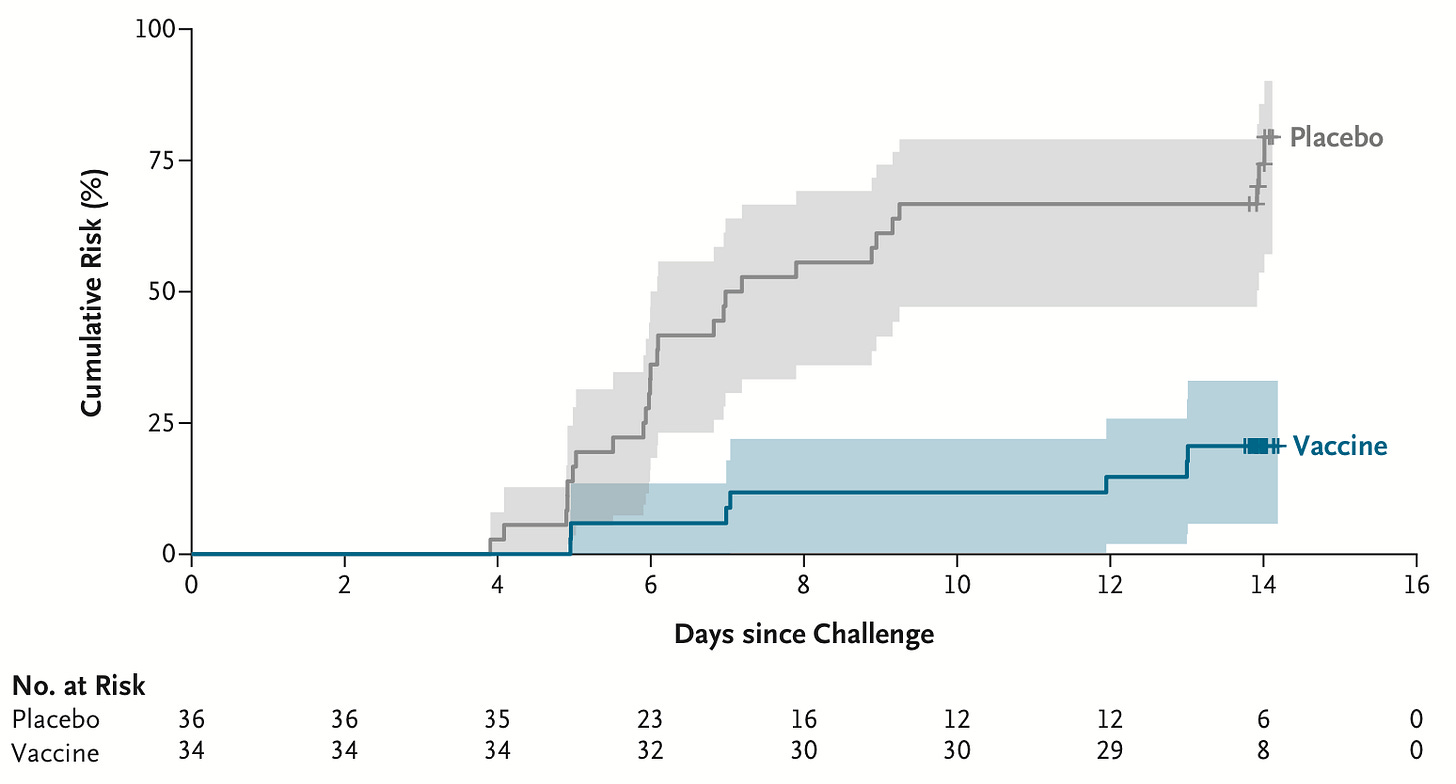

The first paratyphoid vaccine may be on its way. It is a live attenuated vaccine created by deleting two parts of the bacteria’s genome. In a phase 2b challenge trial of 72 participants5, recipients of the vaccine had around a 73% lower risk of infection from Salmonella Paratyphi A. Moderate side effects were somewhat common, though. The researchers want to pair it with typhoid vaccination as part of a broader prevention tool against enteric fever.

The cumulative chances of an infection by S Paratyphi A, which causes paratyphoid fever, in the challenge trial for a new vaccine. In the placebo group, 75% of participants tested positive for an infection within 2 weeks; in the vaccine group, only 21% did. Source: Naina McCann et al. (2025).

Breakthrough patients

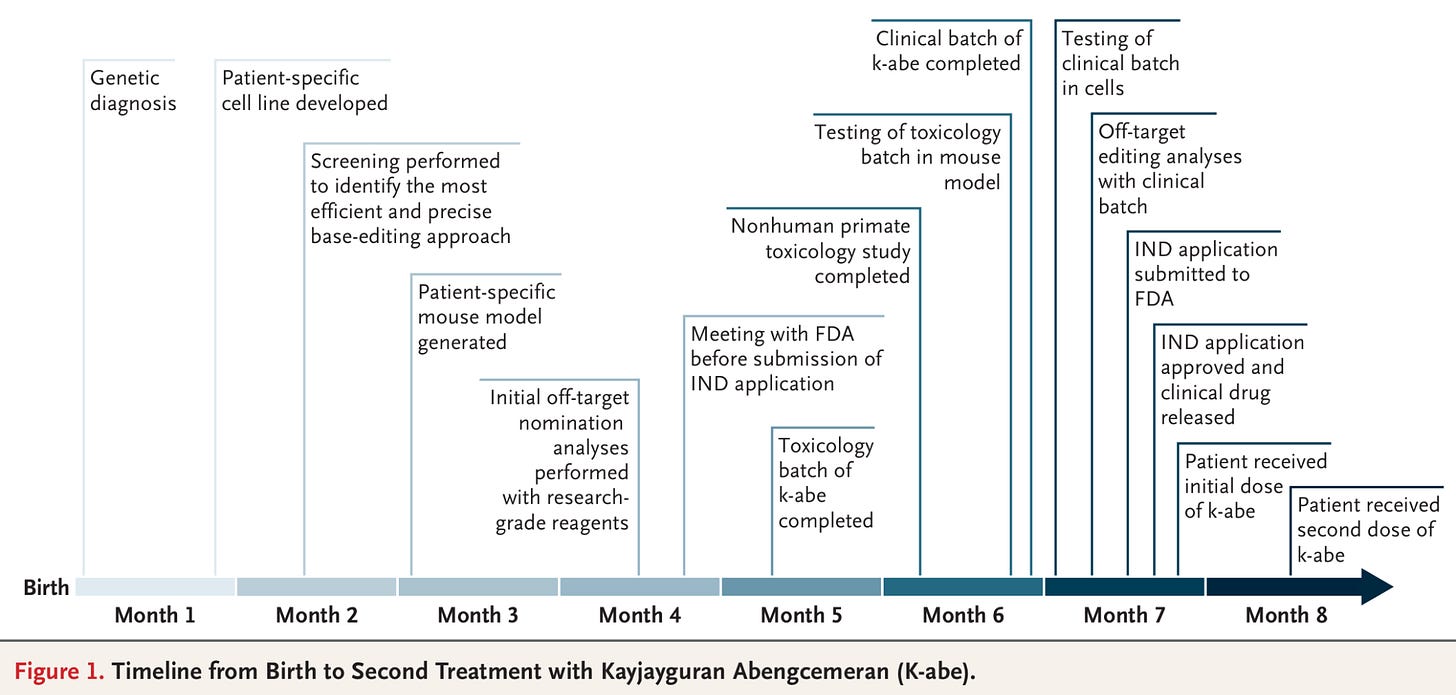

A baby named KJ became the first gene-edited baby6, and the first person to be treated with a custom in vivo CRISPR treatment for his rare genetic disease. He had a deficiency in the CPS1 enzyme, which meant his liver couldn’t convert ammonia into urea, damaging his brain and liver.

Babies with this rare deficiency typically stay in hospital until they’re eligible for a liver transplant, and have to follow very strict diets. In this case, researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia diagnosed him within days of birth, and spent 6 months designing and testing a personalized gene-editing therapy before fixing his deficiency with a CRISPR base editor delivered by lipid nanoparticles. His blood ammonia levels dropped and he began tolerating more dietary protein, gained weight, and reduced his medications. Now 18 months old, he recently took his first steps.

A research team at Roche and Boston’s Children’s Hospital set a new world record for the fastest human genome sequencing and analysis – it took them under 4 hours to perform whole genome sequencing and analysis with Roche’s SBX workflow (see next section). We’ve come a long way since the 1970s, when it took weeks to sequence a single gene, the 2000s, when it took 6 months for a whole genome, or even the 2010s when it took 3 days.

The first human genome sequence was determined in 2003. Since then, it has become faster and cheaper to determine human genome sequences, going from 1 genome in 6 months in 2003 to 20 genomes in 3 days in 2015. Source: Jeffrey A Schloss (2020). In 2025, it now takes under 4 hours to sequence and analyze a human genome. 22 women became the first to receive mitochondrial donation to replace the mitochondrial DNA in their eggs, and have had 8 live births so far. They carried mutations that could have otherwise caused potentially fatal inherited metabolic diseases in their children; mitochondrial donation has helped avoid those worries.

A 42 year old man with type 1 diabetes became the first person to receive a transplant with cells that are gene-edited to hide them from the immune system, meaning he will hopefully not have to take immunosuppressants. In the first 3 months after the pancreatic cell transplant, his immune system showed no reaction to the edited cells, which survived and produced insulin without notable side effects.

A 56 year old man with chronic granulomatous disease, which involves long-term inflammation of the intestine and makes people vulnerable to repeated infections, became the second person ever to be treated with prime editing. It’s a relatively new form of gene editing that can fix tiny but critical errors, such as a single missing base in this case, with high precision.

Research breakthroughs

Roche developed a new genome sequencing method called Sequencing by Expansion (SBX), which expands DNA molecules into larger structures called Xpandomers, which are easier to read. It could improve accuracy and bring genome sequencing costs down further. And as I mentioned in the previous section, the method was recently used to break the record for the fastest turnaround time in sequencing a human genome.

Scientists developed a new gene-editing tool, STITCHR, to insert large pieces of DNA into genomes. It’s based on a highly active retrotransposon called R2Tg in zebra finch7, which they engineered into a programmable system that can insert edits up to 12.7 kilobases long, roughly the size of the average human gene, without errors.

Even longer gene edits, of nearly 1 million bases, became possible with ‘bridge recombinases’, which were discovered by researchers at the Arc Institute. They use a bridge RNA which folds into two loops, one that binds to the target DNA and the other to the donor DNA, before bridging them together. This could allow scientists to edit entire genes, long regulatory elements or clustered gene families, which were previously out of research for CRISPR based tools. Here’s a video of how it works:

Scientists combined AI models RFDiffusion and AlphaFold2 to create a ‘multi-step enzyme’ for the first time, and that enzyme has never been seen before in nature. Enzymes are extremely specific proteins that can speed up reactions; they are widely used in industrial processes, pharmaceuticals, cooking, and consumer goods like laundry detergent; synthetic multi-step enzymes could broaden their uses further. On the Hard Drugs podcast, Jacob and I talked about the amazing breadth of proteins and how AI tools are being used to improve or design new proteins never seen before.

Nanoparticles designed so far have been symmetrical, but now researchers have designed one with different sides, which can interact with different molecules at the same time. These two-faced nanoparticles (hah) could make vaccines, medicines, research tools, and diagnostics more versatile.

DNA vaccines may now be possible. DNA vaccines have many of the benefits of mRNA vaccines (being easy to produce, fast to update, and producing proteins that represent viral proteins closer to their natural form), but are additionally stable at higher temperatures. Until now, they’ve been hard to implement because cells tend to reject DNA entering them. But scientists have created DNA lipid nanoparticle formulations that can package and deliver vaccines, and tested them for DNA vaccines against influenza and COVID in mice and rabbits.

Reading recommendations

If you enjoyed this post, you might like some of these books on the history of science and medicine, a genre that I’ve been reading a lot more of recently. Here were my favourite reads this year.

Genentech: the Beginnings of Biotech by Sally Smith Hughes.

This amazing book traces the development of genetic engineering, and how Herbert Boyer and Robert Swanson turned the science into a commercial product by developing recombinant insulin. This transformed insulin treatment from the extract of tens of thousands of animal pancreases per pound to the product of yeast in bioreactors. And by doing so, they kickstarted the field of biotechnology.

The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris.

Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic techniques in surgery, had a fascinating life that I didn’t know anything about until I read this book. His father, JJ Lister, was himself a famous microscopist (in his free time), and Joseph Lister took forward that interest in microscopy and microbiology. He also took inspiration from Louis Pasteur, who was his contemporary, on germ theory, but played down the theory as it was controversial at the time, instead choosing to popularize antiseptic techniques on their own.

The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson.

I mistakenly expected this to be a somewhat shallow, generic popular science book, but it was a very thorough account of how CRISPR gene editing emerged from decades of obscure basic research into bacterial immune systems. The book focuses on Jennifer Doudna, who pioneered the technique as a medical tool, and her life and work. One thing I thought was great was that Isaacson interviewed many of the scientists involved and tells their perspectives of the same events, so you can make up your mind about the ‘he said, she said’ controversies yourself (there were surprisingly many).

Vaccinated: One Man’s Quest to Defeat the World’s Deadliest Diseases by Paul Offit.

A surprising number of people haven’t heard of Maurice Hilleman, one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century and someone who likely saved hundreds of millions of lives by developing vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, chickenpox, adenovirus, pneumococcal disease, meningococcal disease, Hemophilus influenzae b, and many other diseases. He seems to have been a very funny, and foul-mouthed, guy, but also an incredibly strict manager of his division at Merck. Hijinks ensue.

A History of Immunology by Arthur M Silverstein.

I loved this book. I enjoyed learning about the early, often wildly speculative theories of immunity, how blood groups and allergies were discovered, and the 19th century intellectual battle between the ‘humoralists’ (who believed immunity arose from the blood) and ‘cellularists’ (who believed it arose from cells), which the humoralists largely won, leaving cellular immunity comparatively neglected until the mid-20th century. Another fun point was that some scientists genuinely believed that immunology was more or less ‘solved’ in the 1960s, before the discoveries of T cells or V(D)J recombination.

The book was also fascinating about where the vast diversity and extreme precision of antibodies comes from. It’s a great read for anyone sympathetic to the idea that biology is more theoretical than physics.

Or how about a podcast?

And if you prefer podcasts, may I suggest Hard Drugs, a new podcast on medical innovation hosted by … myself … and my wonderful friend Jacob Trefethen. We’ve recently done episodes on:

and more.

On a more serious note.

I struggled with writing this post this year. If you’re interested in medicine and global health like I am, this has been a fairly terrible year.

The US’s largest global health program, PEPFAR, which supplies HIV treatment to over 20 million people worldwide, faced massive staffing cuts and was completely paused for months, leaving many HIV clinics to shut down.

The economists Charles Kenny and Justin Sandefur estimate that, as a result of the huge cuts to US foreign aid and shut down of USAID, around 500,000 to a million people will have died by the end of this year.

That may sound hard to believe until you realize that the US is the largest international aid donor, by virtue of its size, and that these programs reach tens of millions of people with lifesaving treatment annually. Shamefully, many other countries decided to follow step.

Then there’s the rise in anti-vaccine sentiment and policy, the disruptions to US-funded clinical trials abroad, and the massive layoffs at the FDA and CDC. But expertise takes time to gain, and programs are far easier to maintain than recreate from scratch.

I suppose this isn’t just something of interest to people who follow medicine as an abstract topic.

Medical innovation affects our own lives, the health of people we know and love, and millions of people with friends and families far away even if we may never meet them.

People often describe innovation as a set of specific, sporadic breakthroughs that happen by pure chance or sheer determination, but it’s really much more of a continuous stream every year, like the ones I’ve described here. That stream can be sped up or slowed down by policy, funding, and institutional choices; and real progress – providing the fruits of that innovation to people who need them – takes a huge number of people and institutions working together.

I think it’s up to us to turn things around and to minimize the disruption to science and medical innovation.

Earlier this year, I pledged to donate more than 10% of my lifetime income to highly effective charities, but it feels like a drop in a puddle. If this post inspires you, or someone you know, we could make a bigger difference.

I’m still optimistic about what’s possible, in part because I keep meeting people who are unusually motivated to work on these problems anyway.

But things could move much faster with more people involved, and with effort, determination, and better ideas and incentives. I still think the best days of medicine are ahead of us, but only if we choose to make them happen.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you have a happy new year.

– Saloni

Although chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation were separately practiced much before that, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation techniques were mostly forgotten until the mid-20th century. CPR was introduced in 1960 and found to be much more effective than other techniques.

For cystic fibrosis, this is true for specific genotypes that commonly cause the disease, which are targeted by new drugs such as Trikafta/Kaftrio (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor and ivacaftor).

And the vaccine of course.

Although this number of patients would usually seem small for a clinical trial, challenge trials tend to have much greater statistical power, as I’ve written about before.

This refers to somatic gene editing, not germline gene editing. In other words, the gene editing was done in some of the baby’s cells to treat his illness; it did not modify all his cells, or his reproductive cells, and would not be inherited.

Corrected 2nd Jan 2026: I initially made a typo here and wrote ‘zebra fish’ instead of zebra finch. Two very different animals!

EssilorLuxxotica released a new type of eyeglass lens, branded Stellest, which is supposed to slow down the development of nearsightedness in children. It was approved by the FDA this year and is now in local optometrist offices; it has apparently been used in China for a few years. The study which claimed to slow myopia by 50% or more was done by the manufacturer, and is still being followed up, but it’s looking hopeful at the moment.

https://apnews.com/article/essilor-stellest-glasses-myopia-nearsightedness-c1c04fd52a022860a5654b21e4f68179

Thank you so much. That's awesome! Just did my end of year donation yesterday as well :)